At work, in a dark theatre, I have been watching a cast of college students telling the wild tale of Penny—a millennial “fuckup” who signs up to bike across America for cancer. Along the way she “tries out” every town they visit, trying to imagine a possible version of herself in that place. I emerged from the theatre at 11 pm on Friday night to discover that the towns I love in the western North Carolina mountains were washing away: Black Mountain, Hendersonville, Chimney Rock, Lake Lure, Bryson City, Santeetlah, Murphy, and of course—Asheville. My parents were immediately cut off—I have heard from them just one brief message a day since. They are safe and dry. They have food, but the water is still off. The power has just come on. The neighborhood has banded together to check on each other, to feed each other, and even to flush each others’ toilets by emptying out a jacuzzi one bucket at a time.

At the college, we are staging what we are calling “The Great American Road Trip. On bikes. On stage.” Bike America by Mike Lew takes its place self-consciously in the genre of American travel writing. It references Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, Travels With Charley, and On the Road. Penny is compared to Odysseus, Tom Sawyer, and Walt Whitman. She fails to find either America or herself. Although she travels through the nation’s highway and byways, “back up, and back up and out” at a cyclist’s pace—she still moves too fast and too restlessly to really understand any individual place. She never stops being a tourist because her understanding of America is as a “macrocosm of microcosm” Penny….and Penny doesn’t know who she is.

PENNY: I’m shopping…Shopping the country. For—I don’t know. For where I should live and who I should be. Shopping for a place I can be myself (20).

To Love Places

So many people have reached out to express sorrow for Asheville and to check in on my parents. Asheville is large in the imaginations of many of us in the Southeast—the Biltmore and the beer and the blue ridge vistas. It is our escape from the oppressive heat of the Floridian peninsula. It is our southeast Austin or Portland with its hippies, buskers, and drum circle. I love that so many people love the region. I love that tourist dollars flow into an area so economically destitute and removed from the epicenters of cultural, financial, and political power. I grew up in a different corner of Appalachia further north that similarly had developed a devoted tourism base. The outlying, pitiful towns hobbled along as the resorts at the mountain lake grew bigger and bigger. The tourist money helped…a bit. But perhaps in the end all such tourism can do is to keep the memory of these forgotten corners of America alive a little longer.

“Location Informs on the Self”—Penny, Bike America

I’ve been handling quite a few crises in my new role as Director of Theatre, and my colleagues keep remarking on my calm. In Bike America, Penny’s first shares her theory of what she hopes to discover on this bike trip with Tim Billy. He accuses her of being a “bike away bride,” just using the trip to escape her problems (and her clingy ex-boyfriend), but she counters with the claim, “location informs on the self.” She means that perhaps her problems are a result of the fact that she has always lived in the same few-block radius of her childhood home in Boston. Perhaps, if she traveled:

PENNY: What if I got to be a lady Tom Sawyer. You never get to see a lady adventurer, right, so what if I got to be one. You think that sounds’ dumb, don’t you? That sounds dumb. Never mind.

TIM BILLY: No, it’s just…you also can’t bike.

PENNY: So what? So what if it’s only day two and I think I grew bone spurs? This is America! I want to be the hapless heroine in my own picaresque. I want to see where I fit in to the American landscape, try on each town, live like they live. (20-21)

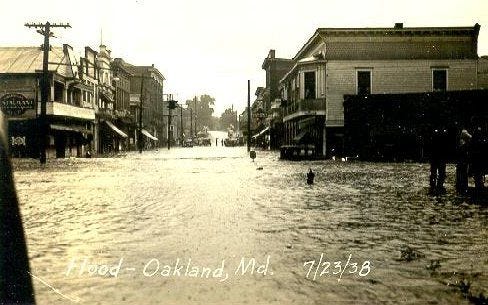

Perhaps I can handle crises with relative aplomb because in my teen years, I spent weeks combing the archives for old photos of Oakland, MD to make digital copies and to create a documentary about the town’s history. That history included frequent floods as snow melt, runoff, and heavy rainstorms frequently wiped out downtown. The series of dams that finally stopped these regular floods were not built until the 1960s.

Maybe my stoic outlook developed because of my connection to places destroyed by flood (or sometimes abandonment). My “song of my self” is a tune whistled on mountain walks through tunnels like this one, when we stumbled upon the Road to Nowhere. When you approach the end of the Road to Nowhere, a rough sign demands that you figure out why the road itself is a “broken promise.” The road stands there as a mute testament to the fact that our America (the country Steinbeck calls a “monster” in Travels with Charley) breaks its promises. I never lived in suburbia, so I never expected life to be tidy or convenient.

I’ve criss-crossed the far west of North Carolina many times. Not many people go to see the magnificent Fontana Dam and read the TVA’s self-satisfied account of how the Depression-era projects “electrified” the South, but if you did, you would realize that the millions of people who now live there, the short-term vacation rentals available on every croppy outlook, and the many beautiful lakes boasting lakefront mountain homes are only possible because of an extensive system of dams and reservoirs. You might then begin to sense how fragile all of that development really is. After all, it has not been even a hundred years since the regular floods were tamed, as depicted in Oh Brother, Where Art Thou.

The Impassable American Landscape

Our land is the monstrous offspring of two warring metaphors, the gods of our beliefs about ourselves. The first is that American progress is inevitable and that American genius is up to any challenge. The second is the American longing to make a home and to create hearth gods and to settle in a place. I hate to say this, but we have forgotten that ours is a land that floods. Like Greek heroes, we suffer from a foolish pride in our technological conquering of the countless streams and rivers of Appalachia. Now, the same foolish energy keeps building Miami, even as it sinks, and perhaps the only way for us to be a people is to have no sense of our history, even going only 100 years back. I pray we aren’t those people but I fear we are almost there. Hardly anyone teaches folk history, folk songs, or folk arts anymore. The photos, the oral histories, the journals: the stories of the impassable American landscape are out there, but—like the Road to Nowhere—most of us don’t even know to look for them. One thing that stands out to me in folk songs is how impassive the people are in the face of immense loss and suffering—such as in this song that I love by Dahlia Low:

River’s rising. Carolina.

Water’s coming down.

River is rising, Carolina.

Water’s coming down.

Move the horses in the pasture

To higher ground.

Move the horses in the pasture

To higher ground.

The water take me down.

Muddy water take me down.

Pa runs out to the field of cotton

To watch it drown.

Pa runs out to the field of cotton

To watch it drown.

From the rooftops to the valley

Watch the water coming down.

From the rooftops to the valley

Watch the water coming down. —Dehlia Low “River is Rising”

I went down to the river to pray

Just a few weeks ago, my parents sent me some photos of their pastor baptizing new Christians in the creek at the community park. I am sure that the creek has burst its banks and the whole park is under water. But the flood waters will recede to reveal the playground equipment, the disk-golf baskets, the picnic tables. Or perhaps it is all washed away—another place where so much of life happened just gone.

At the end of Bike America, Penny realizes in the moments before her death, that she regrets screwing it all up. As she narrates, we see her friends make it to the Pacific Ocean, put their feet in the water, and “mumble platitudes”:

PENNY: I felt these waves of regret at all the time I spent looking outwards, all that deflection when I should have just loved and lived. And I could have loved. Anyone. And I could have lived. Anywhere. Anywhere down that 4,000 mile expanse. (73)

If you are outraged for the Appalachian mountains, it may be regret. Regret that the surprising tunnels, highways, hamlets, and villages may be gone—for you—forever. That brewery you had hoped to try next time, that contra dance you would squeeze into the itinerary, a quick peek at the drum circle before a great dinner at the latest best restaurant after a long day hiking in the mountains.

Go back, though. The songs of Appalachia will keep rising. They’ve survived many a flood. The region shared its songs and its stories with me, even though I was never a native daughter. It will welcome you (back), too…

I’ll see you at the river.