In my previous piece, I pursued the idea of an artisanal shopping experience (manifested in the toy catalogues that have reappeared in my mailbox) that fills a need for both consumer and producer by delivering a forgotten pleasure that internet shopping has been unable to replicate.

Today I want to follow that theme and ask where readers will be able to find what I am going to call “bespoke writing” in contrast to the products of generative AI. Generative AI is helping its users (I won’t call them writers) to flood the world with disembodied text. Disembodied texts are texts produced by algorithms instead of by writing bodies. The behemoth bookseller that broke the publishing economy has recently taken steps to limit the incursion of AI-generated books into the marketplace by limiting authors to self-publishing three books a day on their platform.1 Its marketplace—which has become known for providing us with charmingly wrong counterfeits of everything from soap to Birkenstocks to child safety seats—now has an AI problem. Counterfeit oven gloves are one thing, but counterfeit books? The potential assault posed by AI on authentic authorship actually moved Amazon to act preemptively.

Generative AI is helping its users (I won’t call them writers) to flood the world with disembodied text.

AI-generated writing has thrown academic instructors as well as Amazon into a tizzy because one of the primary ways we assess student learning has been through assigning copious written homework in the form of short response papers and longer research papers. Not only are there no trustworthy tools by which to spot the “fakes,” the best practices that we developed to create assignments, with specific, multi-step writing prompts, will prove our own undoing. I recently looked over a prompt for a “critical thinking writing assignment” for a course I haven’t offered since 2020. I laughed out loud when my colleague pointed out that the carefully sequenced questions in the prompt were tailor-made to be fed into ChatGPT to generate a pretty good essay.

Surprised by A.I.

I was surprised to recognize that I had provided an algorithm for a “critical writing assignment” long before technology had provided the students with a tool to quickly fulfill the objective. I had to engineer an assignment that guaranteed that an average student would produce a piece of writing that scored well for “critical thinking” according to a rubric. The argument about why an expressive arts course needed to produce such a piece of writing had been lost years ago. This tortured assignment had been invented and had served its purpose, but now I was being asked to re-engineer it yet again, this time to evade the use of generative AI (not the student) satisfying the assessment goal.

Which leads me to my incendiary through-line: I was already treating students like computational writing machines by assigning this ridiculous short paper with its ten-question prompt. Students and employees and e-book authors all recognize that what this insane economy of ours is paying for right now are words, not writing. Worse, words are purchased as the pretext for selling advertising. Only a madman would provide writing when all that was asked of you were mere words.

Words, Words, Words

My seminar class this week discussed generative AI as a tool as they develop their careers. Some cited that the various AI text generators have produced some good bibliographies for their literature reviews and that it does well at editing an email to have a professional tone. But most complained that something about the writing it produces seems off, and that “the kids” using it (freshmen) shouldn’t, because they don’t even know how to write yet. Like other “training wheels,” generative AI seems to prevent, rather than aid, the development of basic skills. By producing only inoffensively competent sentences, AI prevents students from the bumps, bruises, and falls of failing at writing. By never writing a terrible sentence, the “kids these days” can’t write any sentences.

But, other students assured me that the technology is still very young, and it will get better and better at understanding what we want it to produce, and soon it will be able to think critically for us.

None of which helps with my fundamental critique of AI-generated writing, which is that I don’t want to read it. AI-generated writing is a counterfeit of human thought; foisting it on readers (even if that reader is a professor) denies the right to pleasure in the reading of texts. There is nothing and no one to know behind an AI-generated text. I see my future being like Hamlet’s, in which my answer to the question, “What do you read, my Lord?” is a vexed cry of “words, words words!”

A book without matter is just words.

The emergence of Substack as a “platform” bespeaks the necessity of “bespoke writing” in a digital age drowning in words. Bespoke opposes “ready-made,” and usually refers to clothes. However, the first recorded use of it comes from 1755 and refers to a “bespoke Play” to be enacted.2 Bespoke clothing in its construction bears some signature of the craftsman in the workmanship, a signature which nonetheless cannot be isolated to be authenticated. We often associate bespoke with couture (meaning expense), but bespoke goods and bespoke writing can be quite humble. The poem that marks the death of a beloved friend. The play requested to commemorate community history. The speech to honor a great victory. What these pieces of writing bespeak (“speak of, tell of, be the outward expression of; to indicate, give evidence of”) is the writer’s presence within a community of signification. Such writing bespeaks (“stipulates, asks for") the presence of writers in that community—writers who might get it wrong; writers who may tell too much truth; writers who may strike a nerve. By subscribing to this Substack, you are requesting writing to be delivered to you. A bespoke writing service, like the newspaper or book-of-the-month, for the digital age and without any advertising.

Writing gets right to the nerve—an access to sensation that artists, philosophers and theorists have recognized for millennia. We say good writing moves us—to tears, to laughter, to action. In , The Pleasure of the Text, Roland Barthes recalls an ancient practice—the actio of ancient rhetoric, which is performed writing aloud—to provide a full picture of the “aesthetic of textual pleasure” (66).3 The actio is “a theatre of expression,” itself not expressive, in which:

significance…is carried not by dramatic inflections, subtle stresses, sympathetic accents, but by the grain of the voice, which is an erotic mixture of timbre and language….it suffices that the cinema capture the sound of speech close up (this is, in fact, the generalized definition of the ‘grain’ of writing) and make us hear in their materiality, their sensuality, the breath, the gutturals, the fleshiness of the lips, a whole presence of the human muzzle (that the voice, that writing, be as fresh, supple, lubricated, delicately granular and vibrant as an animal’s muzzle), to succeed in shifting the signified a great distance and in throwing, so to speak, the anonymous body of the actor into my ear” (66-7).

Barthes is steadfast: we do not need the author’s presence or knowledge of the author’s identity to experience the pleasure of the text. But we do need the grain of the voice in writing. We do not need to pay couture prices to experience the pleasure of handling a bespoke garment that we find in a thrift store—it feels different than mass-produced clothing. Both writing and bespoke goods carry a sensuality, a fleshiness, a whole human presence, a vocal or material signature. In a separate essay titled “The Grain of the Voice,” Barthes draws an equivalence between singing, writing, and dance, all of which carry the bodily presence of the artist into us through the eyes and the ears:

“The grain is the body in the singing voice, in the writing hand, in the performing limb” (276). 4

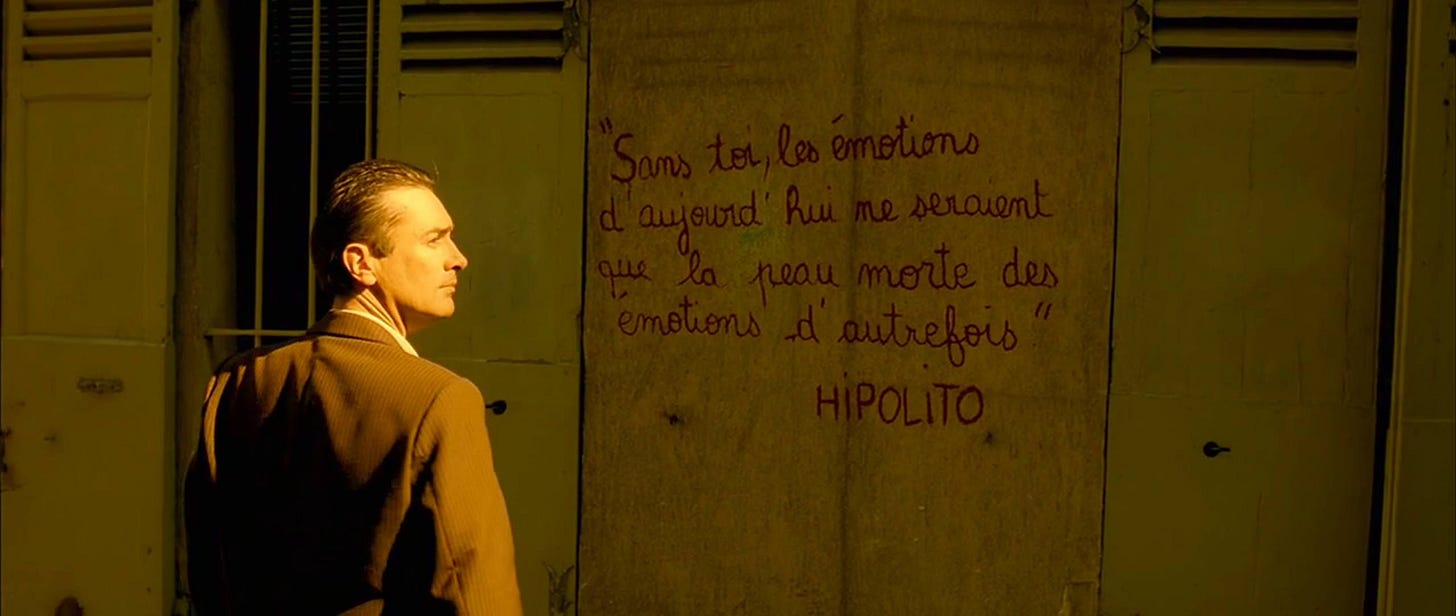

Whether the piece of writing bears the mark in a wavering line in a graffitied scrawl across a public wall, the mistyped text message because of “fat fingers,” the shortened note because of the scratchy pen, the unconscious word choices we make as we adapt our handspans to the keyboard—these writings all have the grain of the author’s voice.

I am demoralized by students using AI to generate their writing because they are withholding the pleasure of reading their texts. But I don’t blame most of them—teachers have replaced writing with word generation; educational goals and assessments have made failure an unacceptable outcome. And there is no score on our rubrics for accidental brilliant infelicities of language. There would be no way to score on a rubric the palpable, granular, panting effort in the paper of a student who struggled all semester to articulate an analysis of a drama for herself.

So, I have hope for writing because so many of my students already reject it. The “literature machines” of AI were imagined long before they were invented, and dismissed by theorists like Italo Calvino, who wrote in “Readers, Writers, and Literary Machines”:

Just as we already have machines that can read, machines that perform linguistic analysis of literary texts, machines that make translations and summaries, will we also have machines capable of conceiving and composing poems and novels?

Calvino immediately claims that such a machine is useful only for what it offers in theory, not as an actual machine because it would not be worth the trouble of constructing it.5

In theory, if I needed to receive 24 B-level essays displaying critical thinking, I would write an algorithm that could produce that. In actuality, I already tried it seven years ago, and the essays were dispiritingly dull. In the same class, students were also assigned a completely open assignment—to produce something creative about a moment of culture shock—imagined or real. They could create a painting, a film, poems, songs, short stories. Each and every piece was unique and bespoke the author’s passion for the project and engagement with the course themes. I have been swept away by the singing voices of business majors accompanying their own lyrics on guitar and shocked beyond words by confessional literature written by sorority girls I thought hadn’t paid a bit of attention. They create beyond what data points can capture.

Bespoke writing is the writing of digital exiles, using the tools of the dominant matrix to create temporary campfires around which to share stories. I’m glad you’ve stopped by our tent to hear a few stories.

Ella Creamer. “Amazon restrict authors from self-publishing more than three books a day.” The Guardian. Sep 20 2023. Link.

“bespoke, adj.”. Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, July 2023, <https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1027354203>

The Pleasure of the Text. Translated by Richard Miller. Hill and Wang. New York: 1975.

The Grain of the Voice: Interviews 1962-1980. Translated by Linda Coverdale. Northwestern UP. 2009.

New York Times. 9-7-1986

AI makes me cringe. But do you know these wildly original words that be spoke by the infamous Kanye West in the song American Boy?

“Dressed smart like a London Bloke

Before he speak his suit bespoke

And you thought he was cute before

Look at this peacoat, tell me he's broke”